Next day (17 June) we rode along the shore and through the wide harvest fields of Oripò, in great heat, which Lear in his sketch of the day has noted — “Oh, how hot!” — “A landscape of pale ochre.” “Mariana in the South” is another of his side-notes, perhaps suggested by the “brooding heat” — “And flaming downward over all/ From heat to heat the day decreased,”[22] or by some statuesque figures of peasant women at work in the fields, whom he has drawn and described in the sketch of today, in their “long, white, woollen vests, fringed with scarlet worsted embroidery,” “chocolate coloured belts” — “three long ropes of hair, with red silk tassels and ends” in the foreground of the harvest field. On the opposite shore were the long line of the white walls of Chalcis, bordering the strait, under “hills in palest lilac,” and the snow-topped cone of Dirphe over-topping all.

Lear’s sketches of Chalcis, the yellow walls and towers rising up from the water on the opposite shore, the Venetian castle and drawbridge at the crossing of the narrow strait, the entrance into the island fort and town of Chalcis, were taken from the shore of Aulis that evening. Later we had a long ride round the shore of the upper bay, and entered by the stone bridge to the Kastro in mid-stream, and thence across the wooden drawbridge into the Castle, under the carved Lion of St Mark, sprawling on its Tower frontage, and into the town.

Two days were spent in Chalcis, “most picturesque and interesting.” All the records of Venetian history have since been swept away by the modern Greeks since 1848.

If the Castle and battlements no longer stand as they then did, another blot is left upon the character of the modern Greek, by the destruction of historical memorials which once marked Chalcis as the chief seat of the Venetian Republic in Greece. The memory of the great siege in 1466, by which it resisted so long Mahmoud the Conqueror, and the merciless massacre with which the Conqueror wreaked his vengeance on the Christian defenders, might have interested the Greeks in keeping up its walls and battlements, even if they were crumbling away past repair.

Lear’s sketches are here, as at Athens and other places, valuable for their preservation of historic scenes and records of sixty years ago, and of what are now lost to sight and memory on the spot. He was sketching here through morning and evening, the town and neighbourhood still retaining some signs of the Turkish occupation, a mosque or two and minarets in ruins, cypresses and fountains, dilapidated wooden houses with overhanging galleries and latticed windows, among the new Greek houses, lying on the slope of the lower hills and on the lower piazzas, and bounded on the plain by the river-like strait above and “the refluent tides”[23] below, North and South of the narrows and the bridge of the Castle.

So he brought in a harvest of drawings, in the evening of the second day, of scenes most picturesque, but in his notes on one {sketch 48} he describes the squalid foreground in which he was working among narrow streets and waste ground, the native crowd and “thistles, rags, shoes, fleas, tobacco leaves, [wood], puppies, straw,” while tender, soft evening lights were settling down on hills and buildings and water.

VIS4483, reproduced by kind permission of Museums Sheffield

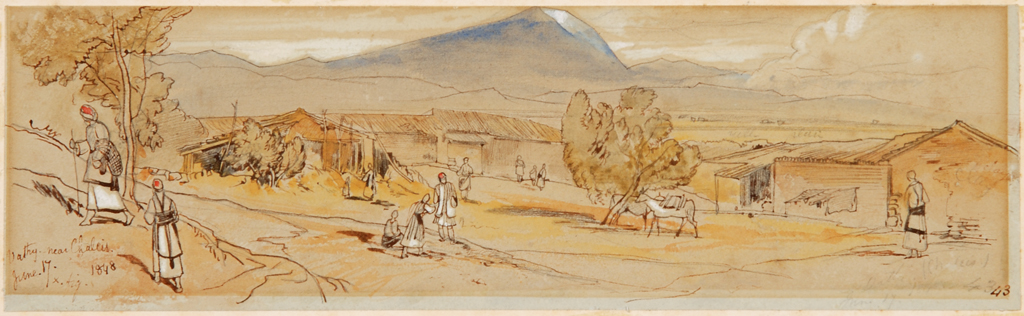

Dressed by sunrise. C. bathed, my bad arm prevents me. It is of little more use now than just after the fall, though it gives me less pain, unless moved suddenly. An encampment of Gypsies amused us till starting; turbaned creatures and trowsered women, rolling about with sieves, naked children, pipes and pipkins. Off by 5 a.m. Flat ground, by the seaside. Site of the Battle of Delium. Hope Socrates did not find so many thistles to walk through![24] After this followed undulating hills by the seaside — clear and blue sea. Sometimes we walked our horses in it, sometimes up or down red, sandy roads (like drives in home-parks), between beautiful round, green sofas of Lentisk and tufts of airy, transparent Sea-pine. The opposite coast pure and cloudless — altogether a very lovely tract of scenery, and with the delightfulest of breezes, though the sun was very hot. One should make a landscape of these scenes all pale yellow, pale lilac and pale blue, and then force the near figures in colour ad lib. C. rode on and I sketched {sketch 43}, walking afterwards to Vathi, where I found Janni, who said his men had disobeyed him. Sate under the tent. C. has gone to bathe. The villages hereabout are very low-roofed, low-walled, rattly-tiled, shaky, irregular, plastery, sticky, furzy, scattery places, all ochre and pale brown, tiles pale ochre-red. The ground around the villages is pale gray and ochre.

My arm is perhaps a little stronger, but it had a fresh wrench to-day, which brought on very great pain. Even if no serious damage turns out to have been caused, it is plain I shall be for a long time disabled. When Church came back, we dined; very enjoyable quiet, not to speak of soup, fish, curried fowl, boiled fowl, and a surprising composition of plum pudding and apricots; coffee and a pipe. Exquisite air — but that one is too old, one might suppose Lotos-eating days were returned!

We did not move till past 3 p.m. It was very hot. Then we came to two quiet bays, Euboea always nearer and nearer, we two riding up and down the hills of projecting promontories, to avoid the corners, and at 5 we got opposite Chalcis — mosques and minarets, bridge and fortifications, and the high mountain Dirphe, with snow-head — very fine. Here we stopped to draw,[25] {sketch 44} and then on by continued unexpected bays. At sunset to the Castle Hill, and the celebrated bridge across the narrow stream, into the Town of Many Streets — most picturesque. Found tea set out in not bad little room. Tea and penning out.[26]

[22] Tennyson, “Mariana in the South”, ll. 77-8.

[23] A reference to the phenomenon of the reversal of flow in the Euripus Strait, and also a common collocation in poetry, e.g. in the description of Charybdis in Pope’s Odyssey, Bk 12: When in her gulfs the rushing sea subsides,/ She drains the ocean with the refluent tides”.

[24] Socrates served in the Athenian army which was defeated by the Boeotians at the Battle of Delium in 424 BC.

[25] It is not clear how often Church also sketched during this trip (some drawings survive from other journeys). “We stopped to draw” may just mean that the party halted so Lear could draw.

[26] Lear sketch very quickly en route; later he would “pen out”, inking over his pencil outlines. Colour wash would be applied last.